Reclaiming Universalism

Can we focus philanthropy to rebuild common ground?

My education and career have been shaped by what the Japanese call 人は人 (hito wa hito) — a recognition that people are people, each carrying equal dignity. That orientation drew me toward diplomacy and intercultural communication, where human rights provided both language and compass. It taught me to look for common ground, to believe in frameworks that could connect across difference.

Lately, I’ve been on a listening journey, trying to understand what I missed in the re-election of Trump. That process has unsettled some of my progressive assumptions and forced me to ask harder questions about where universalism has gone, how it has been contested, and whether it can be reclaimed.

Who owns universalism now?

Universalism once sat firmly with the leftists, now progressives. Human rights, solidarity, equality these were rallying cries of movements that sought to unite across difference. Today, the ground feels less steady. The far left has leaned into particularism and identity, while the right increasingly claims universalism as its own. What was once a radical position now risks sounding like a conservative one.

The shift that happened

The post Second World War period gave us the formation of the United Nations and the Declaration of Universal Human Rights, universalism was the left’s most powerful moral frame. From civil rights to global anti-colonial movements, the language of “all” carried weight: all humans are equal, all deserve dignity, all should be free.

But universalism also had blind spots. Treating everyone “the same” often meant ignoring structural disadvantage and lived inequities. Over time, many came to see universalism as insufficient. What good is a universal right to education, for instance, if whole communities are excluded by poverty, racism, or geography? Particularism, identity-conscious, group-specific giving, became the corrective.

Into that gap, the right has stepped. Conservative voices increasingly adopt universalist language: “fairness for all,” “treat everyone equally” as a way to resist DEI programs, identity-based redistribution, or reparative claims. What was once the left’s rallying cry now surfaces as the right’s counterargument.

I'm not a philosopher, but I need it to make sense of things

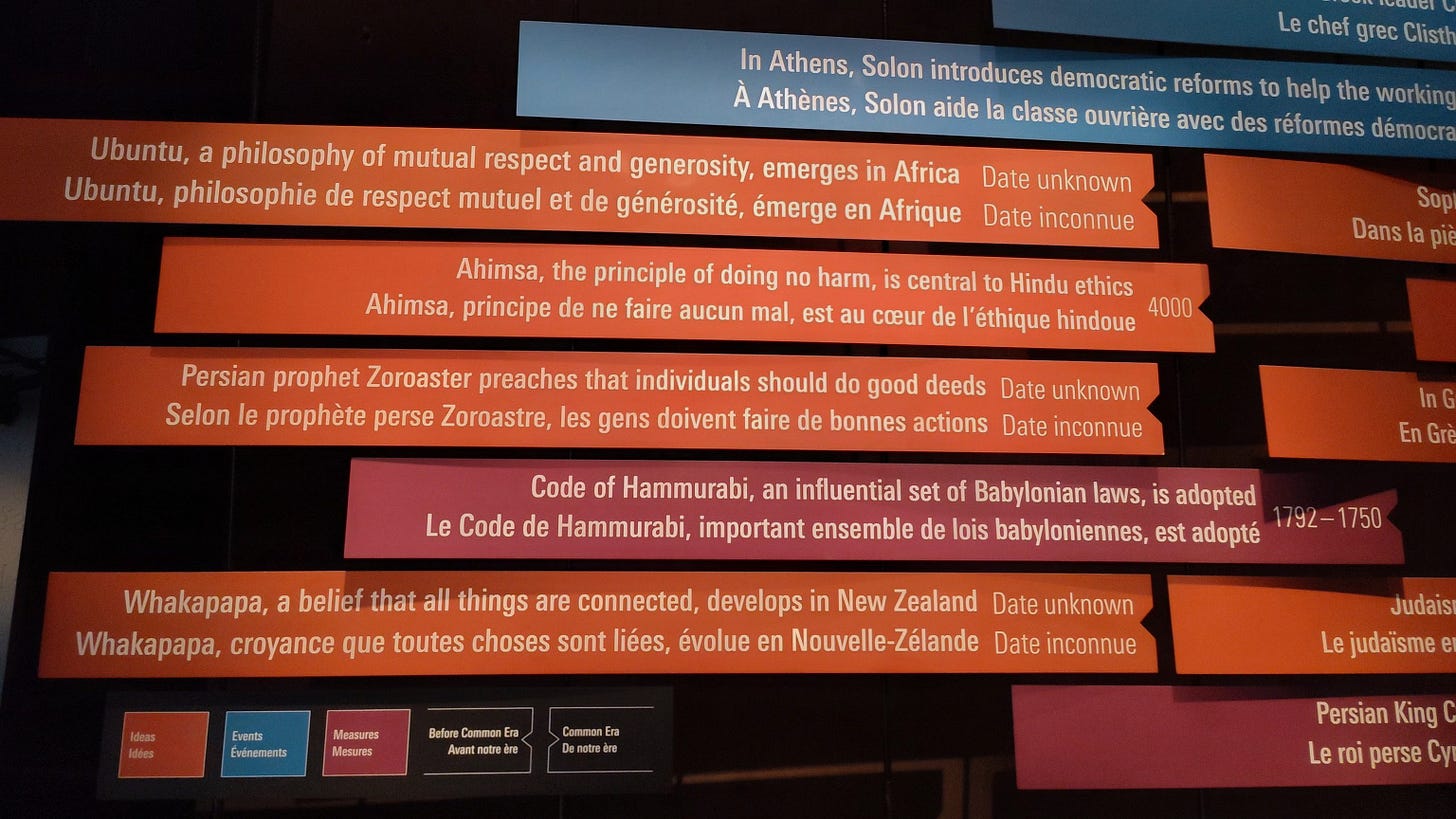

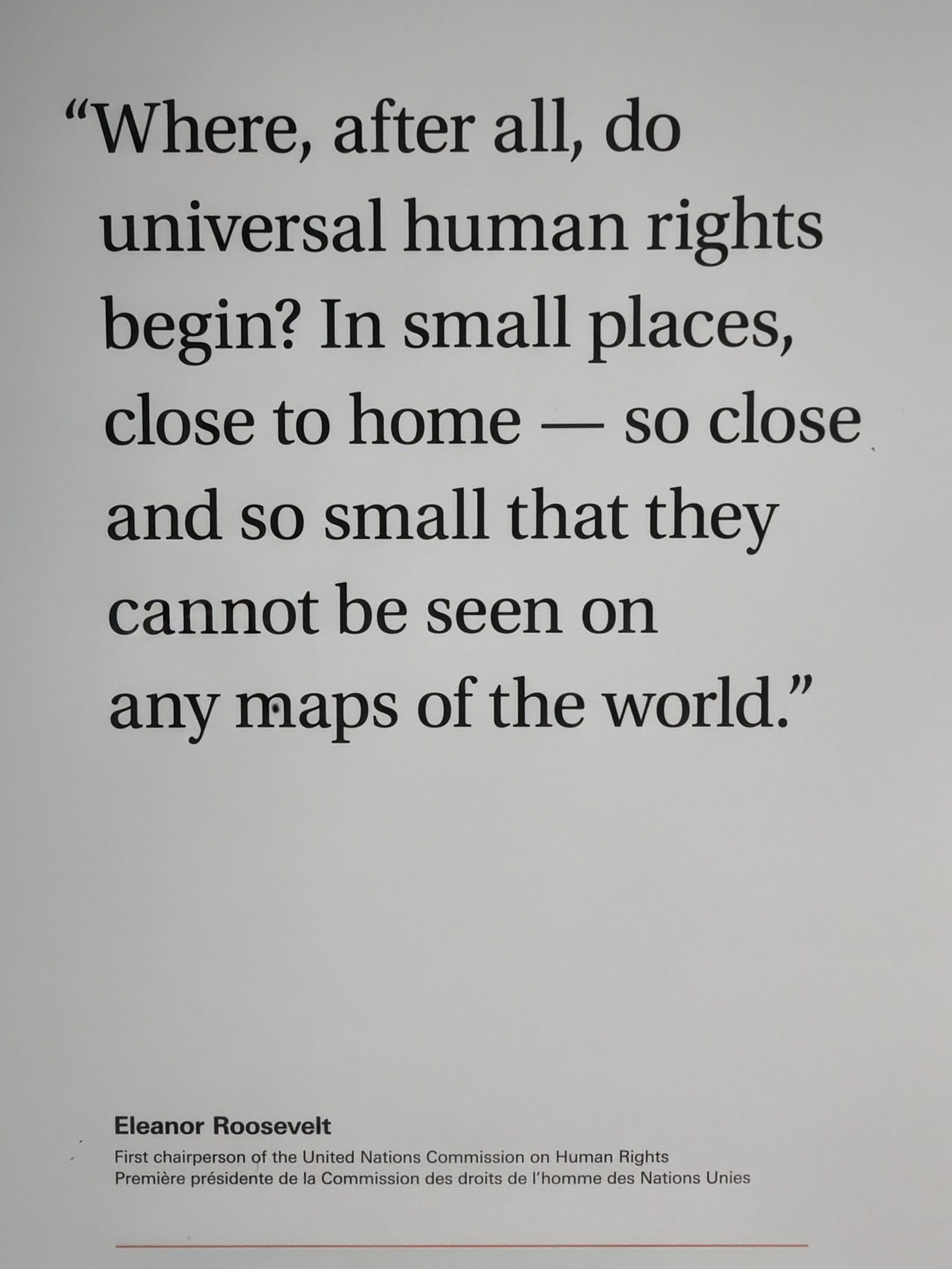

This week, I visited the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg, MB. Inscribed there is the universalist line we all know: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Standing in that stunning space, the message of human rights is not abstract. It lives in the stories told through the exhibits, stories that affirmed the power of universality. The museum makes you feel the force of universalism as an aspiration, while also reminding you that structural injustice persists.

That is the paradox we sit with now: the goal of universalism remains intact, but the practice is constantly challenged by the changing dynamics of particularism.

Towards a Better Universalism?

The philosopher Susan Neiman has argued that the left risks losing its grounding when it abandons universalism. For her, commitments to reason, solidarity, and the possibility of progress only hold if they are built on a universal claim: that all humans are entitled to dignity and rights. Without that, politics risks dissolving into competing interests and endless fragmentation.

Perhaps what is needed is not a return to an older, “neutral” universalism, but a reimagined one, pragmatic, embedded, structural. I am drawn to the ideas that:

The ends are universal: human flourishing, democratic vitality, environmental safety.

The means are differentiated: targeted strategies that account for unequal starting points.

The focus is structural: investment in infrastructures, health, education, climate resilience, civic institutions, that allow dignity to be more than aspiration.

This reframing suggests universalism is not about sameness, but about creating the shared conditions for thriving.

Why this matters for philanthropy

Philanthropy is caught in this inversion.

A purely particularist approach risks fragmentation, accusations of tribalism, and conservative political backlash.

A return to “neutral” universalism risks erasing difference, failing to acknowledge systemic injustice, and losing legitimacy with affected communities.

As Foucault reminds us, power is everywhere and things are not even. The structures in which people live and act are deeply unequal. A universalism that ignores this unevenness is not universal at all.

Neither option feels adequate. Both leave philanthropy exposed, either too narrow to build durable coalitions, or too broad to be credible

What it might look like in practice

Health: Funding Black maternal health could be understood as one pathway to the universal right to safe childbirth.

Environment: Supporting Indigenous land stewardship might be seen as part of the universal good of climate stability.

Democracy: Building civic infrastructure, media, data, civic tech, could be one way to ground the universal right to representation.

Each of these examples is particular in method, yet universal in end. Philanthropy might hold both truths: universality requires targeted investment and targeted investment strengthens universality.

Wrestling it back or moving it forward?

Universalism has not disappeared; it has shifted hands. The question is whether it can be wrestled back, reshaped, or even reimagined altogether. A better universalism may be one that is attentive to structures, open to differentiated pathways, and committed to outcomes that truly include all.

My whole “Listening Tour” and question of what did I miss? has me circling back to what I held dear at the beginning: a belief in human dignity, in solidarity, and in frameworks that help us imagine a common future. The task now is to carry those beliefs forward, not as nostalgia but as material for building what comes next. If philanthropy can help us re-root universalism in structures that truly include all, then perhaps we can begin to shape that future together.

References & Further Reading

Neiman, Susan. Left Is Not Woke. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2023.

Bowles, Nellie. Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History. New York: Thesis, 2024.

de Cuzzani, Paolo and Kari Hoftun Johnsen “Pragmatic Universalism: A Basis of Coexistence of Multiple Diversities.” Nordicum-Mediterraneum: Icelandic E-Journal of Nordic and Mediterranean Studies 10, no. 2 (2015). https://nome.unak.is/wordpress/volume-10-no-2-2015/c81-conference-paper/pragmatic-universalism-a-basis-of-coexistence-of-multiple-diversities/.

Klein, Ezra, and Derek Thompson. Abundance. New York: Avid Reader Press, 2025

This is hugely important, Michele. I’m truly worried by the fragmentation that is happening in philanthropy which I think is falling into the hands of the right. Nobody wants to return to ‘treat everybody the same’ but a constant focus on difference is, if nothing else, wasting opportunities to help multiple people at once.