Foundation Timeframes: Creative options between sunset and forever

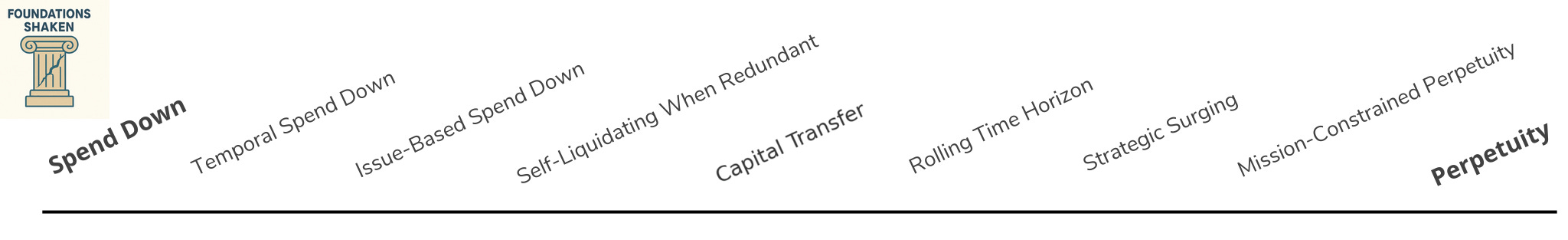

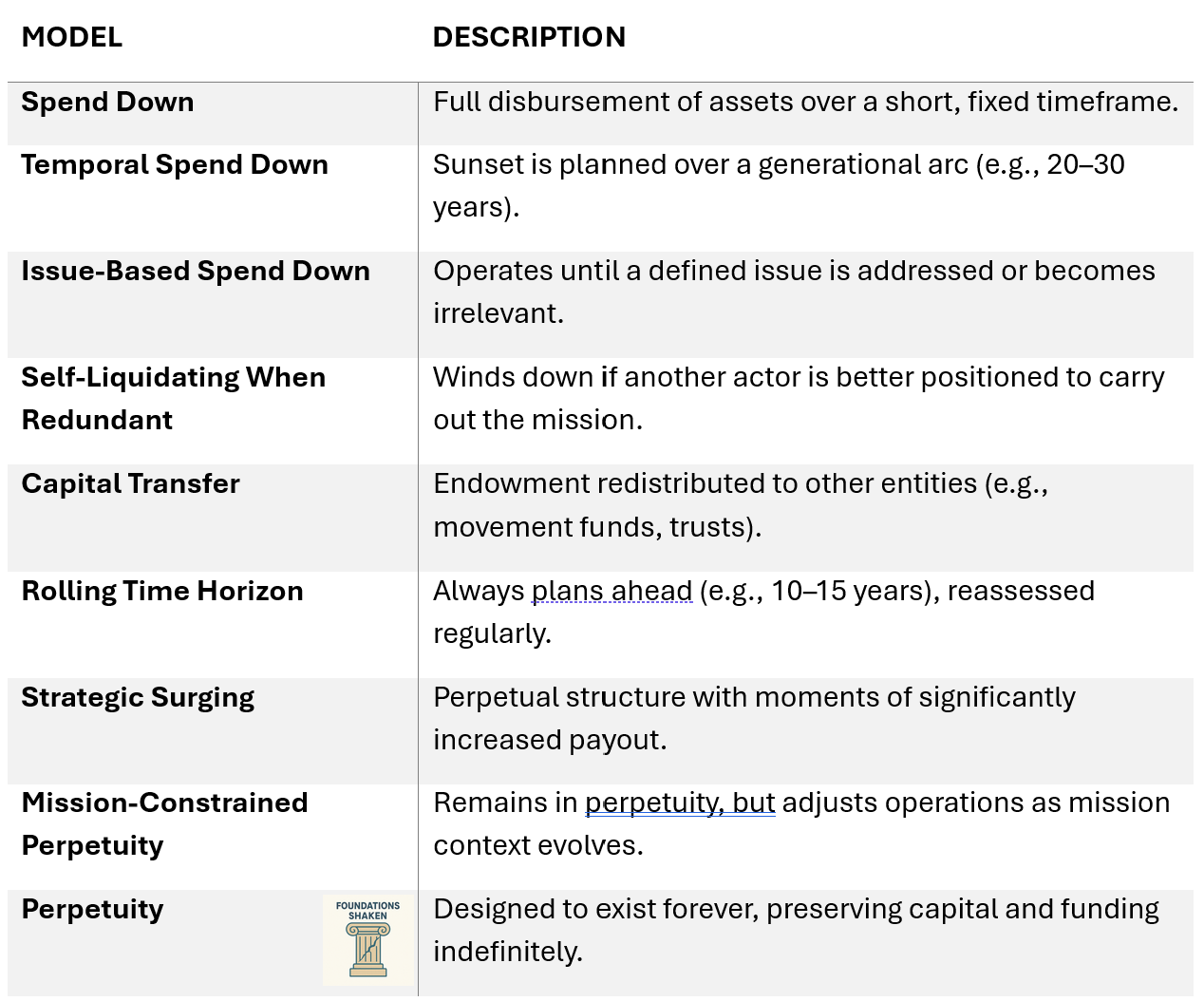

A proposed spectrum of more interesting options

In my work, I’ve been trying to bring clarity to two questions that often get blurred in philanthropic discourse, especially in media narratives that either praise or critique foundations. The first is about how much foundations should give each year: Should disbursement quotas be higher? The second is more existential: how long should foundations last? Should they spend from the principal, eventually winding down their endowments, or preserve them in perpetuity?

This post focuses on that second question. And rather than debating spend down versus perpetuity, I want to explore the more imaginative options in between, models that rethink time, capital, and purpose in more flexible, mission-aligned ways.

Stop the dichotomy

We need to stop framing spending down and perpetuity as a binary. It’s a false dichotomy; these two positions are not inherently opposed, nor do they need to be treated as mutually exclusive. And yet, in our increasingly polarized discourse, the debate often devolves into ideological camps, where one must be right and the other wrong. This posture not only limits productive dialogue, but it also dulls our creativity. I’m not sure how or why the sector turned this into an argument. Frankly, it’s a bit boring. What’s far more generative is the space in between: all the models, strategies, and decision-making logics that don’t fit neatly at either end of the spectrum.

These “in-between” models aren’t passive compromises; they require active foundation management, thoughtful engagement with stakeholders, and ongoing reflection on whether a foundation’s structure still serves its purpose. They demand more from boards and leadership than simply choosing a camp. The middle of the spectrum is often far more dynamic and alive than either of its endpoints. It’s where foundations are experimenting, adapting, and aligning time horizons with mission, context, and community. If anything, it’s the ends of the spectrum that can feel static. The real fun is happening in the middle.

So let’s talk about those options.

A Spectrum of Foundation Timeframes

Let’s Dig In

Instead of forcing a choice between the endpoints, we might ask: What kind of stewardship, structure, and timeline best serve the mission and the moment? I've presented the models in this particular order to reflect a progression from spend-down to perpetuity; however, I'm open to other ways of organizing or interpreting them.

Endpoint #1: Spend Down

Full disbursement of assets over a defined period, after which the foundation closes. Read more about the anatomy of limited-life foundations.

Temporal Spend Down

Decide upfront: 10, 20, 30 years.

This is a planned sunset model, but with a longer arc than crisis-mode spend downs. It enables deeper partnerships and more robust infrastructure investments while maintaining a commitment to an eventual wind-down. Some set a generational clock (e.g., within one lifetime), allowing for meaningful engagement with both founding and successor leadership.

“We’re a 25-year foundation with a mandate to spend ourselves out wisely.”

Issue-Based Spend Down

Spend down when the issue is addressed or becomes unaddressable.

These foundations tie their lifespan to a particular issue or movement. Rather than choosing an arbitrary year, they choose an outcome. This model offers urgency with purpose. It’s most commonly found in time-bound advocacy efforts, policy shifts, or movement-aligned funding. It might even be a portion of the endowment dedicated to existential issues, such as climate change.

“We’ll fund climate justice until there is a just transition, or the window to act meaningfully closes.”

Self-Liquidating When Redundant

The foundation exists as long as it offers unique value; if another actor can take over, it winds down.

Inspired by subsidiarity principles, this model says: “If public systems or civil society take on the work, we step aside.” Although it may not be formalized, it can serve as a guiding philosophy embedded in governance discussions.

“We don’t need to last if our work can be absorbed by others.”

Capital Transfer

Move capital now to others who are better positioned.

Instead of holding assets in perpetuity, this model deploys a foundation’s capital into trusted vehicles, community foundations, movement funds, Indigenous trusts, and donor alliances, especially where local leadership and lived experience offer more responsive governance. PhiLab has great research on examples here.

It is not a “wind-down,” but rather a shift in who stewards the resources and how they’re governed.

“We are a platform for capital transfer. Our endowment is a tool, not a monument.”

Rolling Time Horizon

Adopt a moving timeframe. For example, always plan for a 10-year period and reassess every few years.

Instead of locking in a sunset date or committing to perpetuity, this model operates with a rolling window that is frequently reviewed. It encourages long-term planning without cementing long-term existence.

“We will always have a 10-year plan, but no promise beyond that.”

Strategic Surging

Maintain a baseline perpetual structure, but periodically surge grantmaking in response to windows of opportunity.

Foundations in this category keep their capital base intact but occasionally increase their payout beyond the minimum disbursement quota. Surging behaviour has gained traction and acceptance, as evident during crises (e.g., COVID-19, wildfires) and moments of political opportunity (e.g., Trump 2.0, George Floyd). We can see uplifts in funding in certain years and jurisdictions.

“We exist in perpetuity, but we don't give flat grants. We surge strategically.”

Mission-Constrained Perpetuity

Remain perpetual, but adapt the use of capital and governance model based on the achievement of mission milestones.

The foundation continues indefinitely, but revisits its structure or approach when certain mission thresholds are met. This model recognizes that social conditions and effectiveness shift over time.

“We plan to exist forever, but how we operate will change as our mission evolves.”

Endpoint #2: Perpetuity

Preserves capital to exist indefinitely, granting annually from investment returns.

This is more interesting.

These models illustrate an ideological shift: from preserving the institution itself to becoming more responsive to context. Each decision about time is, at its core, a decision about power, relevance, and adaptability.

So instead of asking, 'Should we spend down or stay forever?' we might begin with better questions: What are we trying to preserve, and why? What does long-term stewardship look like in this moment? And ultimately, what is our foundation’s purpose, in the first place?

When these questions guide the conversation, the discussion becomes far more generative. It moves beyond administrative categories and legal structures, toward the kind of social outcomes that matter most. In this light, a foundation’s approach to time is no longer a fixed identity but an evolving strategy. It is one that aligns its capital, governance, and relationships with the world it hopes to shape. It's a more honest and interesting conversation than “we make grants.”

*I am not presenting a proper literature review on the historical framing of “spend down” versus “perpetuity.” I am aware of important scholarship and sector commentary; please feel free to share key texts or resources in the comments. However, the debate is hardly new (think early 20th-century US rhetoric on monopolies, Rockefeller, and distrust of private philanthropy), even if we often repackage it for the latest high-profile philanthropists making declarations, such as Gates, or others’ sunset timelines.

Others looking in at this discussion may also bring the grantee/grantor binary. The viewpoints of the foundation looking at its purpose and the viewpoint of grantees who seem to only acknowledge foundations as an ATM are also present. This brings an assumption of where a foundation might be in the spectrum you present versus where the foundation thinks (or decides) it should be. Bringing greater understanding of the foundation will move us away from the binary. We often hear that NPO need to get their governance in order, and that may also be appropriate for the foundation.

We could use a renaissance when it comes to nuance. Michele, your piece, and especially the questions it asks, is spot on in this moment:

"So instead of asking, 'Should we spend down or stay forever?' we might begin with better questions: What are we trying to preserve, and why? What does long-term stewardship look like in this moment? And ultimately, what is our foundation’s purpose, in the first place?"